TURKEY AND THE EUROPEAN UNION

The European Summit of 17 December 2004 confirmed that negotiations for Turkey’s accession to the Union will be opened in October 2005. While Europe is in the process of ratifying the draft constitution, the officialisation of Turkey’s candidacy is raising new debates. Already, arguments are flying from both sides. Close-up on Turkey at the gates of Europe.

On the road to membership

Since 1963 and General de Gaulle’s reference to “Turkey’s European vocation”, the links between the EU and the Turkish Republic have continued to grow closer. A member of NATO since 1952, it was in 1987 that Turkey applied for membership and initiated the necessary reforms: abolition of the death penalty, affirmation of freedom of expression, recognition of the Kurdish minority and progress in gender equality. In 1995, the country joined the Customs Union. Membership was the next logical step in a long process.

Heir to the Ottoman Empire, which was dismantled after the First World War, Turkey has always looked towards Europe, although almost 96% of its territory is in Asia. Unlike the ageing EU, the Turkish Republic is a young and dynamic country: half its population is under 25. While some see its 71 million inhabitants as a threat to the EU’s political hegemony, they nevertheless represent an assurance of significant trade opportunities.

Compared to existing member countries, the Turkish economy is doing more than well, growing at an annual rate of 10%. With a working week of almost 45 hours and only 12 days off per year, it is highly competitive in many European markets.

Since the proclamation of the Republic in 1923, official texts have been imbued with the principles of secularism and modernity: the wearing of the veil is forbidden in schools, divorce is authorized, women have had the right to vote since 1934, as opposed to 1946 in France, and abortion is legal (1987). If the threat of an Islamist drift is still present (the 2003 elections brought a radical party to power), integration appears as a way out of the Islamisation of the country, a way to offer a better stability in the Middle East and an opportunity to put an end to the conflict with the Greek part of Cyprus.

After the Heads of State formalised the opening of negotiations, MEPs were keen to have their say on the matter. By a vote of 407 to 262, a large majority supported Turkey’s application. Although this vote was purely symbolic, it nonetheless sent a strong political signal. On the French side, President Jacques Chirac affirmed his “wish” to see Turkey join the European club and thus create a bridge between the West and Islam.

The alternative of a privileged partnership

But the French head of state’s intimate convictions are far from being shared by all. Some voices are indeed raised against the project of integrating the Turkish Republic into the Union.

From a geographical point of view, this rapprochement seems to make little sense since Turkey is located on the Asian continent. Unlike the 10 new member states, its territory is vast, its population very large and it shares borders with Iraq, Syria and Iran, which does not really make anyone happy. By 2020, the country is expected to have a population of almost 85 million, and possibly become the most populous state in the EU. Even if the draft constitution provides for a weighting adjustment in favour of the smaller ones, Turkey’s influence at institutional level would be too great.

With so much labour available, many wonder about future migration flows. Indeed, the lifting of restrictions raises fears of a massive influx of workers from Turkey to other member countries. These transfers could destabilise European economies without benefiting the parent economy.

Concerning the state of progress of reforms, if the Turkish government is taking the path of modernity, the implementation of decisions on the ground remains unsatisfactory. Torture and the condition of women remain problematic, while half of the country’s GDP is still based on the shadow economy and regional disparities are enormous. As for the supposedly secular institutions, they poorly hide the reality of a highly Islamised Turkish society.

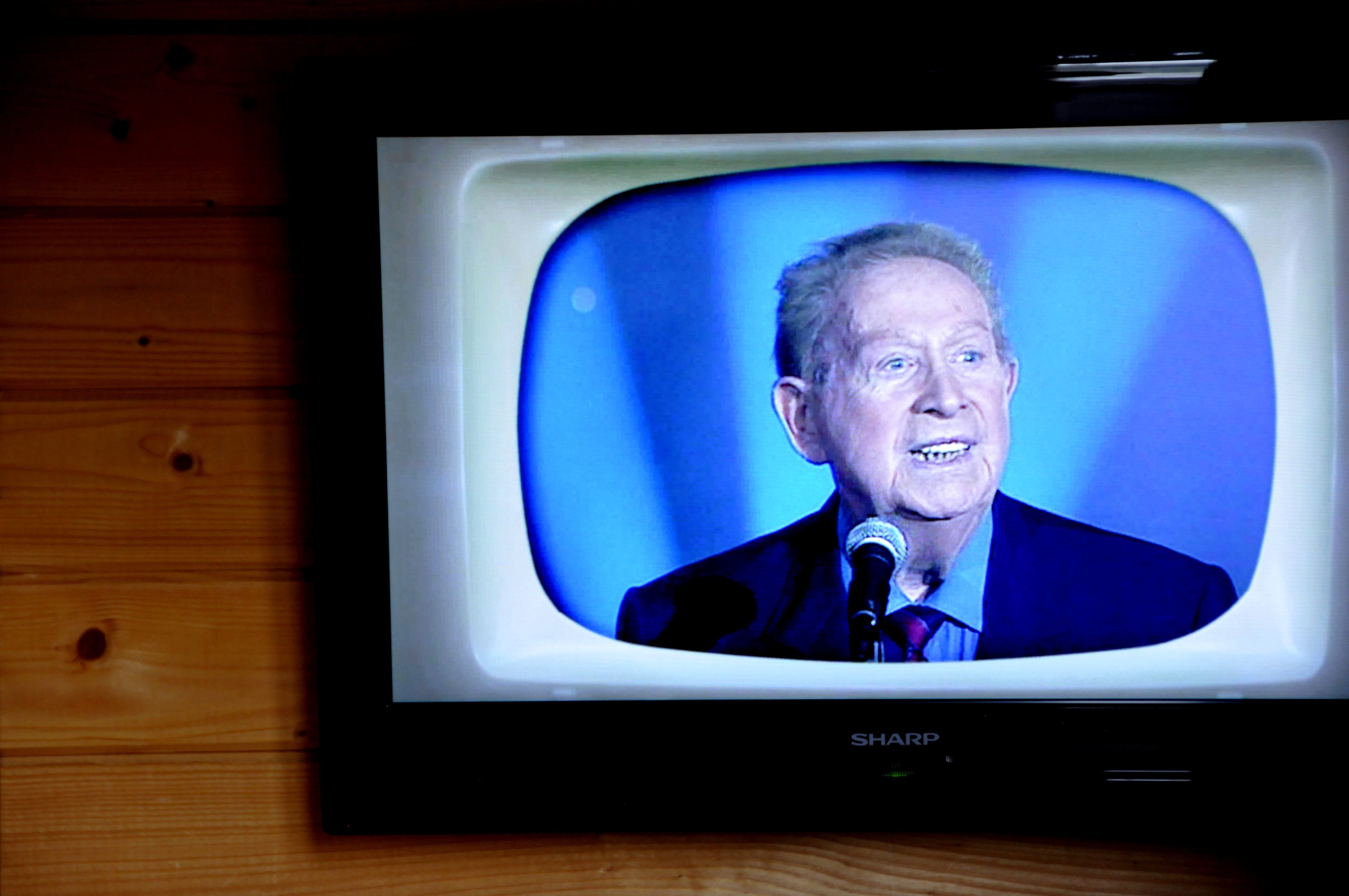

The author of the draft constitution and former French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, former Prime Minister Alain Juppé and UMP President Nicolas Sarkozy are united in their opposition to the position of the French head of state. They consider that Europe must prove that it can function effectively with 25 members before engaging in further talks

The need to set limits also emerges. The former Minister of the Economy explains that “if we accept Turkey as a member, we deprive ourselves of the only objective argument to refuse all the others” – by which he means Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. This ‘argument’ is that of the founding fathers’ desire to make the Europe of tomorrow an integrated political union and not a grouping too disparate to be truly governable. Europe should no longer enlarge, by welcoming new states, but deepen by working on more efficient and democratic institutions.

The French seem to agree with the arguments of those who are in favour of a no vote. A survey by the daily Métro states that only 24% of the French population would be in favour of Ankara joining the EU.

The status of “associated partner” provided for in the European constitution would be preferred by the vast majority of the French political class and by public opinion. An alternative project that Turkey does not intend to accept. President Erdogan recalled that his country would not say “yes at all costs”, other prospects of association with Russia or the United States being possible.

Jacques Chirac thus appears to be alone against all in this fight. While asserting a personal conviction, he nevertheless guaranteed that the French people would have the last word. As the referendum on the draft constitution approached, the Head of State wished to avoid any confusion of the issues at stake: the constitution first, then the Turkish question. Indeed, if negotiations officially open at the end of 2005, they should not be concluded for another ten or fifteen years… What a way to see it through!