Paris Was A Woman

Rome may be the Eternal City, but Paris is the city of the eternal feminine. A certain cast of light and promise of artistic freedom in “La Ville Lumière” has drawn women of words from every country and language imaginable to Paris. There, free of obligations and confines of traditional relationships and social constraints, they collaborated in an extraordinary creativity whose fertility constitutes a rich contribution to the Franco-Anglo-Saxon literary landscape.

While the Left Bank literary culture of the 1920’s and 1930’s has been enshrined as belonging to American expatriate male writers and to Sartre, Gide, and Camus in France, scores of femmes écrivains including Adrienne Monnier, Colette and Germaine Beaumont were collaborating during the same period with Americans, English and Irish women of letters. These Anglo-Saxon expatriates had, like their male contemporaries, been drawn to Paris’ promise of a life spent in creative independence. Yet some of them remained lifelong residents and made their lives more permanent in France than did the men.

“It is nice in France they adapt themselves to everything slowly they change completely but all the time they know that they are as they were,” wrote Gertrude Stein. Her prose perfectly captures the allure of France: while strong family values and rigid social class structure have long-defined traditional society, French intellectual thought equally values artists who forever push at the boundaries that accompany these things. The magnetic pull of a city whose “conditions of its greatness seem to be so basic and constant that again and again something extreme and unsurpassable seems to emerge from them as from the root,” as Rainer Maria Rilke wrote, enriched world literature and promoted cross-cultural literary exchange and creation largely due to women’s ingenuity, determination and networking ability.

One of four books recently published in the United States celebrates the contributions of women writers and artists, and gives us access to the thriving world of literary salons, bookstore openings, and cultural exchanges among women in Paris in the twentieth century.

Paris Was A Woman: Portraits From the Left Bank (San Francisco: Harper San Francisco, 1995) is a book that begins as a documentary film by Andrea Weiss, an American film maker who lives in London. Weiss and her partner, Greta Schiller, spent four years gathering material and funds for the project, which was intended to tell the story of the many “women with creative energy and varying degrees of talent, women with a passion for art and literature, women without the obligations that come with husbands and children, (women who) were especially drawn to the Left Bank, and never with more urgency or excitement than in the first quarter of this century.

It was not simply its beauty but its rare promise of freedom that drew these women to it. They came from as near as Savoy and Burgundy and from as far as London, Berlin and New York, Chicago, Indiana and California.

They came for their own individual, private reasons, some of which they themselves perhaps never fully fathomed. But they also came because Paris offered them, as women, a unique and extraordinary world.”

Weiss explores that world with her collection of anecdotes, oral and written histories, and numerous photographs of the quantities of women who comprised the female literary contingent of Paris in the 1920’s.

While doing so, she also debunks several myths that have been elevated to lies in popular imagination: the myth that the only women in Paris in the 1920’s were the wives of Hemingway, Fitzgerald and other expatriate male writers; the myth that drinking through lazy afternoons in Montparnasse cafés was the only way that writers spent their time; the myth that sexual freedom and exploits were one and the same, and the myth that Paris was only a party scene for most expatriate writers, who immediately packed for America when the first and second world wars broke out.

Weiss shows deftly, through storytelling and photographs, that for women writers in Paris in the 1920’s, sexual freedom did not mean freedom to have sex without commitment, but rather freedom from the heterosexual dictates.

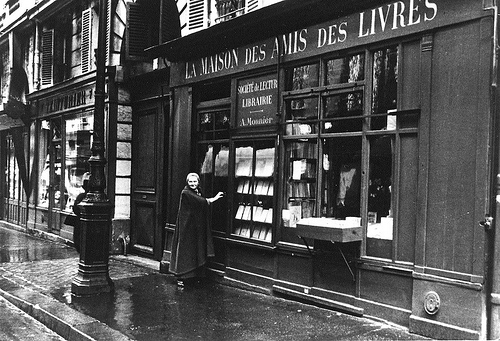

Most women, including Gertrude Stein, stayed put in France through both wars; and their contributions to the Left Bank literary culture changed its landscape forever. Were it not for Sylvia Beach, owner and founder of Shakespeare and Company, James Joyce’s Ulysses, which was banned in the United States, might never have been published in English. Adrienne Monnier’s book shop, La Maison des Amis des Livres, just across from Shakespeare and Company in the rue de l’Odéon, held regular bilingual poetry readings and exchanges. The rich American heiress and famous lesbian Natalie Barney’s literary salons provided opportunities for patronage to women writers whose work might otherwise have gone unnoticed. Gertrude Stein’s literary gatherings in the rue de Fleurus were a hallmark of many literary careers.

Most women, including Gertrude Stein, stayed put in France through both wars; and their contributions to the Left Bank literary culture changed its landscape forever. Were it not for Sylvia Beach, owner and founder of Shakespeare and Company, James Joyce’s Ulysses, which was banned in the United States, might never have been published in English. Adrienne Monnier’s book shop, La Maison des Amis des Livres, just across from Shakespeare and Company in the rue de l’Odéon, held regular bilingual poetry readings and exchanges. The rich American heiress and famous lesbian Natalie Barney’s literary salons provided opportunities for patronage to women writers whose work might otherwise have gone unnoticed. Gertrude Stein’s literary gatherings in the rue de Fleurus were a hallmark of many literary careers.

Although numerous individual biographies of the writers covered in Weiss’ work exist, Paris Was A Woman is the first book devoted to exploring the lives of the women as a group, and the first book to celebrate women’s literary contribution to Left Bank culture.

In the spirit of Franco-American relations and female liaisons, American visual artist Michelle Zackheim devoted several years of her life to resurrecting for American readers the life of one of France’s most extraordinary and least-known writers, Violette Leduc. This contemporary of Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir is little- known outside her native France, where success for her novels came late in life when she was 57 years old.

An artist living in the New Mexican desert, Zackheim began writing her novel Violette’s Embrace (New York: Riverhead Books, 1996) on a dare, when, in a bar, her husband dared her to make the leap to writing, and Zackheim “decided to cast my lot with Violette.” Violette Leduc’s novel La Bâtarde so captivated Zackheim’s spirit that Zackheim flew to Paris, as she puts it, “to find a dead writer.

In the airplane, in the bag on my lap, I carried a lilac-colored copy of La Bâtarde. It was tattered and underlined, with red paper wrappings from chopsticks marking the pages. Many years ago, I had found this used copy in an old bookstore on Broadway in New York. The writer, Violette Leduc, wrote on an edge that reminded me of myself. I bought it for a dollar and devoured it forever.”

Writing in raw, biting, often high-pitched inflections of despair and joy, Leduc was a woman whose soul only found salvation in the social acceptance and acclaim she gained from her writing. Born in Arras in April 1907, Violette entered the world a bastard child. Her mother, Berthe Leduc, a servant and mistress of her employer’s son, Andre Debaralle — Violette’s father — was rejected outright by Debaralle and, in turn, gave Violette the gift of life and very little else.

“My mother never gave me her hand” is the haunting first line of La Bâtarde. From her childhood devoid of love, Leduc fell in love with men, women, and literature — though she only devoted herself exclusively to the latter. Discovered largely thanks to Simone de Beauvoir, who loved Leduc’s work though was driven crazy by her eccentricities, Violette Leduc lived half her life in love with women (including De Beauvoir) and men both homosexual and heterosexual. She forever sought the maternal affection and approval denied her in childhood.

In her book, one of Zackheim’s characters, Lili, describes Violette’s life as the incarnation of “Fluctuat nec mergitur… the motto of the city of Paris. I think it comes near to describing Violette’s life — she is tossed in the waves but she does not sink.” Although Zackheim admits that she probably would not have liked Violette Leduc as a person, Leduc’s language is so “splendid, it is passionate, it is powerful, it is brave….(she) is my accomplice…..her sighs slip through her language.” Her book Violette’s Embrace is her own tribute to this lost writer. A semi-fictional account of Zackheim’s search in France for the pieces of Violette Leduc’s path, Violette’s Embrace will entrance anyone enamored of stories of literary connection and discovery.

The book more than lives up to its dedication “to the return of Violette Leduc” and takes its place among works in English that allow English-speaking readers access to the life and works of one of France’s most obscure and least-known femmes de Lettres.