by: Sheri Mignano Crawford

French Soirée

A Twentieth Century history of the musette accordion and French musette dance music in Paris and the San Francisco Bay Area, and includes biographical sketches of accordionists whose repertoire included the dance music.

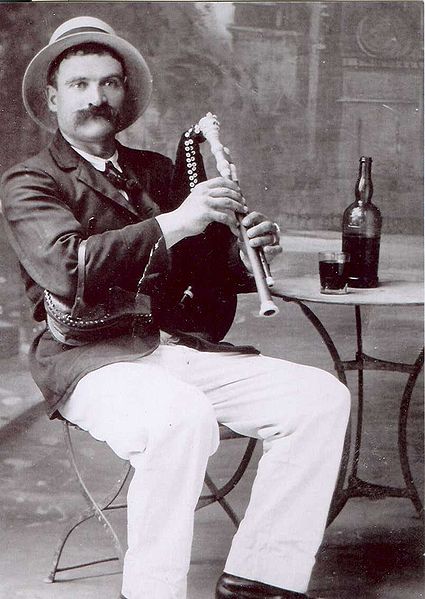

1. musette accordion

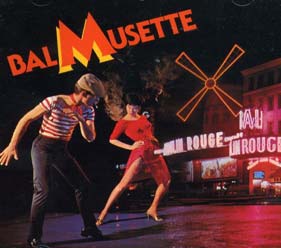

2. bal musette

Here is an audio example of musette accordion from Paris Musette 3CD series available here. Here is my friend François Parisi playing his composition “Annie Zette”

Another example from François Parisi playing his composition “Ballad du Paris” for the motion picture “Midnight in Paris” by Woody Allen

Table Of Content

- Playing with a Musette Switch

- A Brief History of Bals Musettes

- How the Musette Got Its Groove

- San Francisco Bay Area Bal Musette Scene

- Endnotes

Preface

The box has suffered and been maligned almost from the moment it breathed in its first breath. Here are just a few affectionate French denigrations and nicknames: La Boîte à Frissons (The Trembling Box); Le Piano du Pauvre (The Poor People’s Piano); Le Piano aux Bretelles (The Piano with Suspenders).i Whatever you call it, it will respond and transport you to another time and place.

I have attempted to explore the French musette accordion in all its many faceted aspects and give it its proper place in our hearts. It has survived to tell the stories of the Moulin Rouge, the back alleys of Belleville, and the cabaret stages in Pigalle. Its beautiful resonating reeds, its graceful melodic lines, and its bellowing breaths make it a good partner for music and in life. Accordionists embrace it and breathe life into it. We adore the accordion but mostly we love the musette accordion!

One of the best stories about the affectionate relationship some accordionist have had with the musette tuning comes from Vince Cirelli, a local legend whose accordion repair studio, Cirelli Accordion Service, has been a Mecca for accordionists since it first opened in 1948.ii If you have played an accordion in the San Francisco Bay Area during the past few decades, it has probably been repaired by him. He is the living legend with stories that only he can tell.

Vince related how he had loaned a musette accordion to a professional accordionist who had been visiting San Francisco. He returned to report that “everybody on the boat enjoyed it.”iii When Vince found that out, he no longer wanted it. Apparently, the gentleman had taken it out on a cruise in the San Francisco Bay. Salt air damaged the steel reeds and in time Vince knew he could not sell it. Ron Flynn, who had conducted the interview with Vince, took it home anyway, and indeed, eventually the reeds rusted.

Accordions are delicate creatures! However, the abuse level depends on how little you play, more than how much you play. An accordion in its box might as well be in a coffin. That’s why it is important to “faire le boeuf.” Or as the Zydeco accordionists like to say it: “Laissez les bon temps rouler!” Find friends and jam.

Playing from sheet music is good; unfortunately, so much of the old music is in sad shape due to generations of copying, and the music itself, short of flying to Paris, is next to impossible to find. That’s one reason for the compilation in the Dance Index. In addition, not all of us can carry hundreds of songs in our heads as the often illiterate accordionists did a hundred years ago. Learning to read music is absolutely essential for a deeper appreciation and to achieve the music’s full potential. We can learn new songs and bring them along to a jam session and pull them out decades later to revisit—as old friends.

This eBook is meant for free distribution. But it comes with a caveat. Please don’t play the music in a vacuum. Understand its origins and you will better appreciate those who have spent a lifetime keeping it alive and well. Thank you and I hope you enjoy this little adventure through “La Vie de la Musette!”

PLAYING WITH A MUSETTE SWITCH:

A Revolutionary Act?

I have been a Francophile since 6th grade when I was able to take my first French lessons. It was coupled by my beginning studies on accordion. They complemented well. Many of the dances were in the musette waltz style (also known as Italian ballo liscio).4 Music would become my focus for my entire life as a result of my early education.

In college, my French minor helped me to work for the United States Information Agency. It took me to Montréal, Québec in 1967 where I became a bilingual guide inside the United States Pavilion. My French was never any good but my love of the culture flourished. In the summer of 1989 I was able to fully enjoy being a Francophile at the French Bicentennial. I lived in the 7th arrondissement and spent most of my summer in revolutionary related activities and fun, as well as in cafes, at the Paris Opera, museums, a tour of the sewers, bars, cemeteries, and a trip to the nearly completed Bastille Opera. Paris was filled with all types of entertainment on the streets and in the old haunts.

As I watched Philippe Petit walk on a wire across the Seine from the Trocadéro to the Eiffel Tower, I was transformed into a French citizen. He read from “Les Droits des Hommes” as the loudspeakers carried it to tens of thousands of listeners. Some were in tears, others simply intoxicated. The festival mood kept everyone busy and happy.

Shortly after returning to the Bay Area in 1998 from a short hiatus, I stumbled into Boaz Accordions. It was just around the corner from where my sister (who also plays accordion) and lives on the Emeryville-Berkeley border. Boaz Rubin and his wife Judith were definitely hoarders as well as deeply involved in their commitment to keep the accordion alive and well. His repair shop was just a small part of how he and Judy worked to elevate the status of the beleaguered accordion.5

One of his first apprentices was Skyler Fell who apparently first started working with him somewhat as a volunteer. When she approached Boaz about learning the repair business, he was only too happy to educate someone from the younger generation.6 The transmission of this knowledge has included an apprenticeship with the Maestro himself, Vince Cirelli. It is crucial that the proper maintenance of the musette tuning be cared for by experts. No amateurs allowed.7 I have great respect for those who can operate on an accordion with the Skill and precision of a surgeon.

Boaz also apprenticed with Cirelli and from Gordon Piantanesi.8 In one of Boaz’s pamphlets he stated a call to action: a paragraph from the prison diaries of Sir Irius Mashin.9 It was a cleverly written plea to accordion players to use a “…socialist musette tuning…” His theory was that a musette switch is a proletariat act against the bourgeoisie. Rubin’s persona urged people to sing and dance out of tune and play with the dissonant musette switch so as to bring about anarchy because “dissonance is threatening…and so playing with [a] musette switch is a revolutionary act.”

While there is no historical evidence of this ever occurring, it certainly has provided me with a compelling introduction to my brief history of the musette.10

Musette 101

The musette name itself also derives from an older small bagpipe-like instrument that was played in the center of France, especially in Auvergne. Musette still refers to s small backpack used by soldiers and people alike. Basically, the valse musette (triple-meter dance) is a blend of folk music from Auvergne with a light Parisian style of dancing popular at the end of the 19th century.

Accordion switches allow the accordionist to achieve various timbre, thus producing an evocative ambience. A Bassoon or Bandonéon switch is perfect for tangos. The clarinet or oboe switch is usually heard with more delicate melodies. Accordions do not arrive with the switch unless it is installed at the factory or a special request is made to modify the accordion so as to ‘borrow’ a switch, converting it into a musette. The piano accordion should always be played with a musette switch on if in the performance of bal musette dancing.

Many accordionists request and prefer the Italian musette tuning, rather than the French tuning, since it is not quite as discordant. The musette switch sounds as though it is slightly out of tune in its “wet” vibrato resonance. One reed is tuned sharp and the other tuned flat to create a quavering due to the vibrating frequencies. These reeds become even more out of tune with the other reeds.

French and Italian musette is heard, more often than not, with a specific dance genre, the triple metered waltz.11 The music itself is written with certain common melodic and harmonic techniques including the following characteristics: Melodic embellishments are often used with arpeggios, especially triplet figures, and ornamentations or grace notes precede a new melodic phrase; glissandos are often heard at the dramatic conclusion in a tango-musette genre. Rhythmic juxtapositions of three against two are also popular and eighth note triplets as well as eighth notes in duple meter.

Will it matter if I don’t have a musette switch? Will I be unable to play the dances? Of course not. If played with expression, joyous exuberance, sensitivity, and grace, the musette waltzes will sound great. But there is a caveat: once you have played a beautifully tuned accordion with a musette switch, you may never return to the dry-tuned, concert accordion.

A Brief History of the Musette Music and the Bal Musette

The musette-tuned accordion music is immensely appealing, evoking the romantic cafes, sidewalks and dance halls of Paris. It contrasts major and minor in its structure, often using parallel major-minor relationships (rather than harmonic minors). If one plays in A minor in the “A” section; then, it will often be followed by A major in the “B” section. The “B” section is usually the ‘spinning” or triplet part, sometimes called la toupie.

If there is a trio section (“C” section) it will generally be played in the original minor key or a closely related key; it is a more relaxed section where the dancers can come closer together. The basic form is similar to a mazurka: A BB A C A. This structural form is instantly recognizable, with its minor keys that shift the emotional response to a sad, nostalgic ambience, often coupled with jaunty triplets, and embracing melodies in the major section.

Most often the harmonic structure supports the melody; it also can provide a counterpoint melody. “Le Petit Valse” exhibits this tendency. Occasionally, in the musette-manouche music, it can display fleeting chromatic dissonances. In particular, the energetic French javas (somewhat like the energetic Mexican jotas) use parallel keys and sound better when played in “one” rather than a fast triple meter. These one-step dances and fast waltzes reveal the resilience of the human heart as it faces perennial heartache and disappointment in the final minor section (which is almost always the return to the first section of the piece).

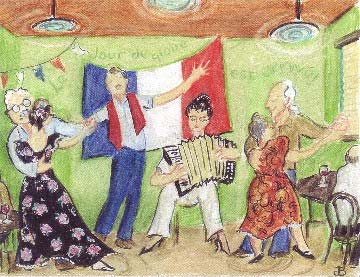

In the 1880s and the arrival of actual leisure time in society, the French guinguettes (public dancehalls) became the popular outdoor drinking establishments. It took a few decades before the accordion arrived in Paris and its environs. These venues provided musette bands to entertain and draw a crowd. Afternoon and early evening soirées enabled mixed social classes to mingle, lubricated by alcohol consumption (often absinthe or grenadine mixed with something stronger) while breaking through the social and economic barriers.

In the 1880s and the arrival of actual leisure time in society, the French guinguettes (public dancehalls) became the popular outdoor drinking establishments. It took a few decades before the accordion arrived in Paris and its environs. These venues provided musette bands to entertain and draw a crowd. Afternoon and early evening soirées enabled mixed social classes to mingle, lubricated by alcohol consumption (often absinthe or grenadine mixed with something stronger) while breaking through the social and economic barriers.

Most public dance halls did not charge admission; instead, men purchased tokens minted by each of the bals (dance halls). Five sous was the price of a dance so one purchased only as many as might be needed. These worthless tokens were made out of cheap metals but you could buy a dance (and maybe have a little fun on the side).12

In Paris and its suburbs, these en plein air venues provided artists like Renoir and the other Impressionists with the reflection of light from nearby rivers and the fluidity of the dancers. Not all public dance halls were illuminated: some were in stark contrast. The rough areas of Paris, like Mémilmontant, Belleville, and Pigalle which might only have gas lit dancehalls and open for business only at night. The dark world of the Moulin Rouge and its class of women (the demimonde) offered acrobatic entertainment, jugglers, exhibition dancing, skits, and special secret hideaways for a clandestine rendezvous. The guests and entertainers all roamed on the fringes of society and talked about visiting “Paname” a pseudonym for the darker side of Paris. Within the Pigalle arrondissement (also known as the Red Light District) some catered more to the “mulots”13 the ‘mice’ or regular crowd than to the more upscale cabaret crowd or the musette society.

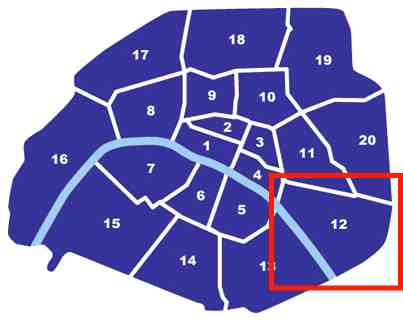

Still the musette was heard in all these various venues and on the streets of Paris that led to the guinguettes. The birthplace of the bal musette is generally accepted as the Bastille district also called the 12th arrondissement. Dancehalls saturated both the 11th and 12th districts. But the accordion would have to travel far from its original home in Vienna, its birthplace. It was there that the accordion would begin its journey. Paris would become its home while the dancehalls became its permanent address.

Still the musette was heard in all these various venues and on the streets of Paris that led to the guinguettes. The birthplace of the bal musette is generally accepted as the Bastille district also called the 12th arrondissement. Dancehalls saturated both the 11th and 12th districts. But the accordion would have to travel far from its original home in Vienna, its birthplace. It was there that the accordion would begin its journey. Paris would become its home while the dancehalls became its permanent address.

Vienna had long been well established as the waltz capital of the world by Johann Strauss. Victorians found it pleasant but by 1900, the Gay Nineties had kicked up its heels. The fin de siècle ignited a new sense of liberation as personal and sensual expression culminated with the unleashing of the Freudian Id and the First World War. Waltzes were no longer just in long, flowing gowns.

Vienna had long been well established as the waltz capital of the world by Johann Strauss. Victorians found it pleasant but by 1900, the Gay Nineties had kicked up its heels. The fin de siècle ignited a new sense of liberation as personal and sensual expression culminated with the unleashing of the Freudian Id and the First World War. Waltzes were no longer just in long, flowing gowns.

The Viennese Waltz King and the painter Gustav Klimt created the swirling rhythms and patterns of this intoxicating period but it would not last long. Maurice Ravel, Stravinsky, and others were the first to break ranks and abandon the lilting waltzes of the dance halls to concentrate on the erotic impulse in their concert hall. Still, the dance halls were heavily populated and dance bands brought in the ‘vulgar’ instruments, so to speak. Banjos, banjolins, mandolins, guitars, violins, and accordions fueled faster dancing and excited the dancers in new ways.

It was Viennese citizen Cyrillus Damian who may have come up with the prototype of the accordion in 1829. These small portable button boxes made little progress and few improvements until late in the century. They were amusing little boxes for those who could not afford a real piano but that would change with technological improvements and a couple of Italian brothers who debuted the piano accordion in San Francisco.

It was 1910 when Pietro and Guido Deiro, (often cited as the two brothers who elevated it in the United States) introduced it on the West Coast. It had been invented in a little town called Salto Canavese outside of Turino. Whereas the diatonic and chromatic easily portable button box (especially concertinas) lacked volume for the most part and were not that versatile, the piano accordion was be built larger, with stronger steel reeds and bellows, and it proved to be more capable of providing a versatile rhythm with its melody.

Once the piano accordion debuted in the dance halls of San Francisco, it was not long before dance bands put it front and center here as well as in Paris. As the Italian accordion manufacturers began to populate North Beach, every home had an accordion. This Italian community pulled together to survive the 1906 earthquake and to open music studios where the new wave of immigrants learned to play a new instrument as well as the old concertina.

Ragtime and vaudeville may have competed in the fun and entertainment field but the accordion was everyone’s favorite instrument at summer picnics and dance halls.14 Music catalogs were saturated with arrangements, marches, and polkas but they also expanded the dancehall’s favorite couples’ dances: the one-step, fox trot, mazurka, waltz, and java. The Latin dances would have to wait until the 1920s to establish themselves but they sneaked into the bal musette as pasos dobles with musicians such as Django Reinhardt.

How The Musette Got Its Groove

Italians were arriving with their luggage and their button boxes. Italian immigrants in the south of France, particularly Marseilles, brought their talents and banked on their abilities to give them reliable employment. Naturally, this invasion of Italians was frowned upon by many Parisians. Antiimmigration attitudes prevailed as Italians tried to assimilate during the first decade. The accordion battle was to take place against one of the most respected, beloved folk instruments to arrive in high society, the cabrette (bagpipe). It descended from the musette de cour and had a long history in the dance genre.

Italians were arriving with their luggage and their button boxes. Italian immigrants in the south of France, particularly Marseilles, brought their talents and banked on their abilities to give them reliable employment. Naturally, this invasion of Italians was frowned upon by many Parisians. Antiimmigration attitudes prevailed as Italians tried to assimilate during the first decade. The accordion battle was to take place against one of the most respected, beloved folk instruments to arrive in high society, the cabrette (bagpipe). It descended from the musette de cour and had a long history in the dance genre.

Alas, the Darwinian forces worked against the cabrette. It had not evolved or technically been improved since its inception. On the other hand, the musette- tuned accordion evolved and vied for dominance; ultimately, it would win. By the 1910, it had displaced the cabrette almost entirely. Here’s how it happened:

In that first decade, a fortuitous encounter with a world class cabrettaire (Antoine Bouscatel 1867-1945) and a family of Italian immigrant musicians, the Péguri family, produced a dynasty through the marriage of Bouscatel’s daughter who married one of Félix Péguri’s sons.

Félix had opened an accordion factory and sold accordions in Paris starting in the early 1890s. He sold all types including diatonic and chromatic button accordions. Péguri’s three sons Charles, Michel, and Louis went on to compose, front bands, and perform. They catapulted the accordion into the bal musette bands.15 Two sons became bandleaders in the manouche period.

The Italians had to work hard at being accepted. At first, fierce resistance brought about a racialist attitude. That “despicable accordion” was brought over by those “Ritals” (meaning Italians). The denigration subsided when Cabrettists reconciled, some learning to play the new musette. They had reason to be fearful. The accordion was bigger, louder, and starting to technically evolve. The cabrette had not improved in hundreds of years.

By the time the descendents of these immigrants from various provinces and countries settled in Paris, dancehalls were already beginning to enjoy the sounds of the musette accordion players: Émile “Mimile” Vacher (d. 1969), Joseph Colombo, Marceau Vershuren, and Émil Prudhomme were some names that brought about that positive change in attitude.16

Originally, the musette sound was associated with the cabrette, a small goatskin bagpipe; it was one of the most popular folkdance instruments in the 19th century. The comparison of bagpipe to accordion is puzzling. These two instruments seem to share only one thing in common: bellows. That shared characteristic puts them in the wind instrument category but one would be hard-pressed to call the bagpipe an actual forerunner of the accordion; nevertheless, the concept of pushing air in and out of the bellows is hard to ignore and the musette resonance is unmistakably similar.

Auvergnat immigrants from central France brought the ‘bagpipe’ musette with them when they abandoned the agricultural life for a chance at being middle class shop owners in the urbanized cities. Some even operated the dance halls which featured the country dances: bourrées, polkas, mazurkas, and, above all, fast waltzes or what the French call javas. There are several etymologies for this word.

The Java dance got its name from a dancehall in Pigalle, Le Rat Mort. Musette accordion pieces are often written as a java, a fast dance. Lou Casalnuovo, fellow Sicilian accordionist, gave me a manuscript titled “Sogno di Java.”17 Java does not refer to an island, nor is it coffee. Evidently, according to one source, it is dialect or a corruption of the French “Ça va?” or “How’s it going?” “Ça” is pronounced “Cha” in Auvergnat, and that might have sounded more like “Jaw.” Thus, this fast, somewhat vulgar waltz may have been dubbed Java. It may have derived some chassé steps from the Italian mazurka as well.

In the 1900s just as the musette accordion appeared in urban centers, brought by Italian immigrant workers, the Java dances were epidemic. One of the most famous Italian immigrants from Marseilles arrived in Paris in time to take advantage of the musette dance craze as well. Vincent Scotto (1876- 1952) went on to write some of the most memorable bal musette songs including “La Java Bleue.” The American singer Josephine Baker and Parisian Edith Piaf debuted, sang and danced to his music.

Finally, it seemed that the discrimination against Italians would subside. With so many Italian composers, musicians, accordion manufacturers excelling at what they did, the French music circles had to acknowledge their prodigious contributions to the musette repertoire.

When the variety of dances expanded between the two World Wars with the java and the apache18 (pronounced ah- PAHSH), the dance halls became a melting pot of desire fueled by laissezfaire attitudes so prevalent during the Roaring Twenties. These types of ‘dirty dancing’ included simulated violence to women in the form of slaps and punches, as well as the sexually charged, intertwining, hands-on one’s partner’s derrière. It was de rigueur.

The Young Turks who replaced the Victorian dandies would swagger onto the dance floor to the delight of the ladies of the evening. This quasiunderworld with its coded signals and gestures came to typify the sleazy demimonde of the public bal musettes. The association and history of dancing, midnight pleasure, and crime dates back to at least the time of the French Revolution in the Bastille district.19

The Young Turks who replaced the Victorian dandies would swagger onto the dance floor to the delight of the ladies of the evening. This quasiunderworld with its coded signals and gestures came to typify the sleazy demimonde of the public bal musettes. The association and history of dancing, midnight pleasure, and crime dates back to at least the time of the French Revolution in the Bastille district.19

With the 1930s, a world wide depression introduced greater use of legal drugs such as marijuana, cocaine, and other intoxicants. Jazz musicians used these to enhance improvisation skills. If you were reading a basic chart, you could experiment with the motifs, straying from the basic line but keeping up with the unpredictable ad-libbing.

Once jazz infiltrated the musette dance halls, the lively swing style and the graceful vals musette coalesced. If you prefer, they clashed and created an eclectic challenge for musicians and for dancers alike.

In the late 1930s, the fusion of Swing and Jazz produced an exotic influence known as Manouche. This word derived from the Romany culture, the roaming, homeless gypsies who lived outside society’s laws and customs. Violins usually took the lead, incorporating jazz improvisation. Manouche or a gypsy style playing melded with Swing and musette. In the triple meter this often meant that the ‘up beat’ would be the strong beat, rather than the “down beat.”

It featured a rhythmic strumming associated with the banjo and provided an accompaniment to the many nonwritten melodies. Django Reinhardt (1910-1953) and Stéphane Grapelli (1908-1997) started their careers buskering and in musette bands in Paris before they ‘invented’ the more chromatic, bluesy style of jazz manouche.20

Unfortunately, the musette accordion couldn’t bend the notes in the same way as a guitar so the accordion disappeared from many jazz manouche bands, staying in the back alleys until Edith Piaf discovered it and legitimized it on stage during her cabaret shows. If there is an official musical instrument of France, it probably became the accordion during this period. Finally, the accordion got the respect it deserved when Edith began to feature extremely talented accordionists such as Michel Emer and Tony Murena.

Edith Piaf (1915-1963) began her career on the streets of Paris and singing in the bal musettes. It is often said that her ‘voice was rinsed in the gutters of Paris.” She was fortunate to be discovered, worshipped, and adored by a Parisian impresario Louis Lepleé who could afford to hire the finest for her concerts.21 She paid tribute to her low origins and to its hard-working musicians and accordionists on stage.

One of her signature javas was L’Accordéoniste composed by accordionist Michel Emer (1906-1984). He became one of Piaf’s favorite accompanists. She enlisted and acquired more musicians as she broadened her repertoire. Marguerite Monnot, Charles Dumont, and Norbert Glanzberg were Piaf’s stable of composers and pianists. They all carried on the tradition of bal musette even as the style morphed with Swing and Jazz but she never forgot the musette feeling. Angel Cabral’s “La Foule” is an example of a dizzyingly fast java.

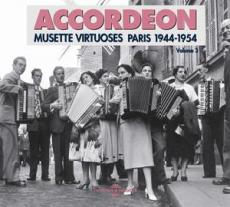

The musette accordion was perfectly suited for the waltz, even more so than piano. Accordion wizards like Gus Viseur, Tony Murena and Jo Privat took to the road to promote it outside of Paris. Viseur was one of the most prolific performers who stayed true to the original musette concert. Others traveled to the United States and sat in with the Big Bands. Americans fell in love with the music, the musicians, and the optimistic energy. They could not get enough of the happy-go-lucky Parisian lifestyle. The songs arrived on the Hit Parade, Jukeboxes, and the weekly radio and television shows. Right through the 1950s, the accordion was the most popular instrument.

The virtuosity of these button box and piano accordionists can be fully appreciated in the gathering of France’s finest accordionists in the photograph below which was taken at a popular club in Paris. It is no wonder that the Lawrence Welk show on American television placed the accordion in the center of its weekly music variety show. The Squeeze Box was sexy! But it was male-dominated as the photograph only shows one female accordionist, probably Yvette Horner.

(Back Row: Yvette Horner?)

Although from the 1960s onwards, rock, disco and newer dance music marginalized the musette accordion, its style survived remarkably well. Charles Aznavour and others have kept it in their chanson repertoire. The musette button box went on to infiltrate and adapt itself to Louisiana’s Cajun, Zydeco, and even French Rockin’ Boogie dance music. It remains a preferred keyboard choice in Italian ballo liscio performances and recordings, too.22

The future of bal musette depends upon open-minded, informed teachers and performers who can demonstrate its beauty, grace, and virtuosity. The legacy will be that a younger generation can learn how to take the bal musette style of music across several platforms and still maintain the integrity of its origins. The global connectivity provides educators will access to it as well.

With the advantage of World Wide Web, it is possible to be entertained 24/7 with non-stop musette songs.23 With so many influences, it remains firmly rooted in the classical waltz, infinitely suited for jazz, and endearingly appropriate as dance music for all festive occasions.

San Francisco Bay Area’s Bal Musette Scene

While the Italian communities cultivated the comparable ballo liscio (smooth dancing) music to an art form in the San Francisco Bay Area, the French immigrants had not been quite as successful. For several decades, North Beach sprouted dozens of dance halls where the couples dancing music could be heard but French venues were few and far between.

Even though the Alliance Française had opened its doors in 1889 for French classes, the French community had always been relatively small when compared to the en masse immigrations from other European countries.24 Still, it has helped to promote social events where musicians and dancers can enjoy the legacy of bal musette.

Traditionally, it has been cafés and restaurants that have provided what little French music is heard but rarely were the venues for public dancing. One of the most memorable venues was Le Montmartre on Broadway, in San Francisco’s North Beach. Françoise Allemand opened it after the war and it ran successfully for more than three decades. In 1979 accordionists Mike Corino and Tom Cordoni produced a live recording that included several musette dances.25

In the North Bay, the wine culture produced a home for French and Italians alike. In 1904 Al Rossi, an Italian Swiss immigrant opened Little Switzerland in Sonoma County. Its waltz- polka calendar is full and the tri-lingual Alpine communities still arrive on weekends to enjoy the traditional dances.26 In Paris, the Tyrolean bal musettes included multi-instrumentalists who would also perform basic circus acts and clown around as well. The “Lil Swiss” does not provide that type of entertainment but it is certainly a venue based on the Parisian musette prototype.

The co-mingling of polkas and waltzes has enabled the new owners to thrive and serve a more modern, diverse crowd. What isn’t surprising is that quite a few Italian composers crossed over easily to the bal musette style. The mandolinist-guitarist Pete Tarzia (1908- 1981) composed in the bal musette fashion using the idioms so essential to the style. His “Echoes of Paris” is still played at Caffè Trieste. Michele “Mike” Corino (b. 1918) an Italian- born accordionist whose prolific compositions include musette waltzes, has contributed to its vitality and played them around the world. He fronted his own bands, taught accordion students, and operated the Corino School of Music on Columbus Avenue in North Beach.27 His “Una Notte a Parigi” is representative of a valzer musette genre.28

A younger generation of accordionists arrived to carry the torch. Since the 1990s the Berkeley based group “Baguette Quartette”29 has captured the attention of everyone. With its versatile repertoire and brilliant performance by Odile Lavault on her 4 row chromatic button box, bal musette will not suffer any demise any time soon. Her ensemble has excelled at recreating Rive Gauche and Pigalle’s Parisian café scene. They strive to provide a theatrical verisimilitude to complement the music. Her mise-enscene presentations often involve a realistic background to give her audience an even greater authenticity. Whether she is performing in front of a Silent Screen classic in the Castro, St. Alban’s Episcopal Church in Albany, or Rancho Nicasio in Marin, her virtuosic technique is flawlessly impassioned with panache at each touch of the buttons. She has almost single-handedly preserved the musette tradition.

More recently there have been memorable Hollywood and European celluloid contributions. These much loved musette waltzes and javas are given new life in an old context. French film has helped in that regard starting in the 1930s with “La Belle Equipe.” Some music scores and composers are stretching the tradition to fit a more contemporary audience. For example, the big summer film hit of 2001 was Amélie. Brittany-born composer Guillaume Yann Tiersen (born 1970) has sustained the musette flair in some of his pieces, including the title hit “La Valse d’Amélie.” In 2007 “Ratatouille” featured jazz accordionist Frank Marocco’s jazz manouche-musette renditions while Chef Linguini worked in the kitchen with the assistance of a culinary rat.

In the North Bay, a recent transplant is the gravelly voiced, talented Michel Saga whose French Barrel Organ makes the rounds at the local farmers markets, French wineries, and summer picnics. He’s produced a couple of CDs with bal musette at the center of his repertoire.30 Michel has also renewed the jazz –gypsy manouche fusion in his band “Rue Manouche.” Based in Sonoma, they present the old Django feel while keeping the bal musette tradition alive.

Another local addition to the bal musette scene has been the talented accordionist Robert Lunceford and his trio “Un, Deux, Trois” with Lisa Iskin, guitar and vocals, and Josh Fossgreen, guitar. Currently, they perform in local Santa Rosa café venues and accordion clubs.

Chanson and musette accordion team is comprised of Dave Miotke (accordion) and chanteuse Hélène Attia.32 Both musicians have recreated the Parisian cabaret ambience with a basic script and songs. They draw from Marguerite Monnot, Vincent Scotto, Jacques Brel, among others. In 2008, they brought the French Café to life in one evening at the Marin Theatre Company where the staged soirée played to a packed audience.33

Even more recently, Due Zighi Baci (Two Little Gypsy Kisses) has been producing its own multimedia cabaret shows to sold-out crowds. When tenor Michael Van Why completed his music degree at Sonoma State University, his recital concentrated on the French classical repertoire. Soon after joining Zighi Baci (my ever-evolving now fourpiece dance band) in early 2008, Michael became a distinguished tenore lirico singing Neapolitan classics in the

bel canto tradition of Beniamino Gigli and Claudio Villa. Soon he and I began to augment the repertoire with French chanson to complement the Neapolitan and Italian canzone.

The French repertoire includes all of most memorable songs from Piaf’s best composers, Armenian born French vocalist/composer Charles Azanavour, Claude-Michel Schonberg, Jacques Brel, and classic standards from Cole Porter and Jerome Kern. The interdisciplinary shows introduce the audience to the meaning behind the French and Italian songs and educate the listeners so that a greater appreciation is gained through the use of a narration, art slides, and images that explain the text.

The broadening collection of European Café songs has blended well and provided even more opportunities to perform in concert settings.34 Due Zighi Baci also has integrated repertoire in its much loved “A Panini on a Croissant” which ran for several months at the French Garden, Sebastopol. “Vive La France”, “Gypsy Serenade” and “Cafe Bohème” have been well attended Fourteenth of July events. The Romance language mix challenges both musician and vocalist in new ways. This decision to develop more of the French dance repertoire and incorporate French chanson has enabled us to explore a much broader repertoire.

Due Zighi Baci continues to shape the evolution of bal musette by including pre-show dances with accordionist Xavier de la Prade. Just as Piaf brought her snappy javas and mournful songs to the streets of Paris, Due Zighi Baci has been bringing these songs to a younger audience who may have never heard of these songs. We showcase Piaf’s stable of composers such as Charles Trenet, Marguerite Monnot, Charles Dumont, and Vincent Scotto whose numerous songs were adopted by so many Parisian chanteuses including Josephine Baker.

Due Zighi Baci is a duo of simplicity and with vocal and accordion complexities. The diversity in its repertoire has renewed the dance traditions in France’s popular late 19th century guinguettes. Whether it’s a waltz from a Jean Renoir film (“Complainte de la Butte”) or an intoxicating java from Michel Emer, Due Zighi Baci and so many others continue to provide a great service by sustaining the vitality of French café music that for so long was languishing.35 Together, the bay area is well served by so many great musicians who strive to recreate the charming, energetic bal musette style.

Vive La France !

EndNotes

i Mary Blume, A French Affair, pp.128-130. Written in 1984, her anecdotal chapter provides some insight in the use/abuse of the accordion.

ii Flynn, Davison, Chavez. The Golden Age of the Accordion. p. 74. Vince’s successor, technician Skyler Fell, opened her shop in San Francisco c.2006.

iii Ibid, p. 142.

4 See pp. 30–31. The Italian equivalent is ballo liscio (smooth dancing) or couples dancing

waltzes, mazurkas, polkas etc.

5 https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Yes-Accordions-The-squeeze-box-is-making-a-2885490.php

6 www.accordionapocalypse.com For more details about the encounter with Vince Cirelli, Pietro Deiro, and Mike Corino.

7 John Reuther. Accordion Repairs Made Easy. O.Pagani & Bros. 1956. Reprint Ernest Deffner Publications, Meneola, NY. The Chapter on Reeds begins on page 49

8 Personal interview, July 19, 2008. Penngrove, CA.

9 Boaz Rubin. Accordion to Boaz: The Hot Air Collection. Berkeley, CA. November 2001. It was first published in the monthly newsletter of the Accordion circle of the East Bay. A caveat appeared on the first page from the Editor, Boaz’ wife, Judy Rubin: Please don’t take any of it seriously, but do enjoy it.

10 Rubin wanted a law requiring accordionists who play block chords to register with the federal government. (Not a bad idea at all if you ask me).

11 Henri Ducharme, an accordion teacher at Boaz Accordions, in the late 1990s taught wonderful classes that introduced students to specific techniques and styles. www.henriducharme.com

12 Michael Dregni. Django: the Life and Music of a Gypsy Legend. Oxford University Press: 2004. (The opening chapters are especially relevant.)

13 AKA “guinches” or the low-lifes; also refers to seedy places to dance.

14 Flynn, Davison, & Chavez, Golden Age of the Accordion. Flynn Publications: Schertz, TX. 1992. This book provides a series of biographical sketches, background, and firsthand accounts of the pioneering decades of the accordion in San Francisco.

15 Michael Dregni. Django: The Life and Music of a Gypsy Legend, chapters 2-3.

16 A fairly complete Index of names by the decade can be found in the Appendix along with the dance halls.

17 “Dream of Java” This dance is included in the sheet music collection. Lou passed away in 2010.

18 Apaches (AKA julots) also refers to Belleville’s gangsters and low-lifes.

19 Claude Dubois. La Bastoche: Bal-Musette, plaisir et crime 1750-1939. Editions du Felin, 1997.

20 Michael Dregni. Django: The Life and Music of a Gypsy Legend, chapters 2-3.

21 I strongly suggest that one read Piaf’s halfsister’s book, Piaf. Simone Berteau presents a raw, unvarnished truth about the struggle to survive. he sanitized version of this book ws the basis for the film titled Piaf. The biogrpahy is remarkable for its audacity, honest portrayal and it is gritty to the core.

22 My mandolin ensemble’s repertoire remains rooted this genre. See pp. 30–31.

23 http://delicast.com/radio/France/La_Yaute_Valse_Musette

24 Claudine Chalmers. French San Francisco. Arcadia Publishing: 2001. Mainly photographic but with a good overview.

25 “Live at Le Montmartre”, San Francisco 1979. Author’s copy. Some bal musette songs on the CD include Petit Fleur, Domino, Le Gamin de Paris, River Seine. Corino used a Cordavox without the musette switch. A complete list of his compositions is in the Corino biographical sketch chapter.

26 www.lilswiss.com 19080 Riverside, Sonoma-El Verano, CA

27 Please see my other book, Mandolins, Like Salami, for a more complete biography and music catalogs. The ballo liscio dances are discussed at length. www.zighibaci.com.

28 A complete list of his compositions is located in the Corino biographical sketch.

29 http://www.baguettequartette.org/

30 Michel Saga sings Songs of Paris, Vol I. Volume 2 has been recently released.

31 No photos were available at time of printing.

32 http://heleneattia.com/

33 Crayon drawing by Janet Baer.

34 www.eurocafemusic.com

35 France has exported some edgy groups like Negresses Vertes, the Garçon Bouchers, The Tête Raides and Paris Combo. Listen to “Café Parisien” for a fine musette collection (a lot of Gus Viseur) and a little history behind it all.

What about in Canada? Especially since Quebec is a French Province?

Well there is a very important Accordion Festival in Montmagny many know about here.

And they give an important part to musette accordion with French players regularly invited.

There is also Mario Bruneau.

Mario is the author of THE ACCORDION GUIDE. He also specialize in musette accordion and history.

thanks you! any good book suggestions on the topic?

There is a good Radio Streaming Station that have a Channel about French Café music.

Note that in USA, people call musette accordion music “French Café” music.

Here is the link to Radio Tune

https://www.radiotunes.com/cafedeparis

This a brilliant article. Thanks so much.

During a recent trip to Northern France I bought more than 300 old 78 records from a junk dealer. (I own a wind up gramophone)

Some of them go back to the early 1900s….most are from the 1930s and 40s.

A lot are accordion players including Charles Peguri. I knew nothing about musette until I started researching based on the records I have. Thanks once again.

bob walker

Thanks Bob,

It would be interesting to investigate further in your 78 records collection.

I am interested.

Maybe we can post some of them here.

best regards

PS contacted you via private email

Yes… A great idea… This era of French music is so rich in melody and sounds… Great to see a site like this and to discover so much about this music. Thanks again.

Brilliant… Thoroughly enjoyable and informative read… Fascinating music, players and instruments. Thank you for this.

You’re more than welcome Terry.

Maybe we should add some audio examples as well.

What do you think?

Comments are closed.